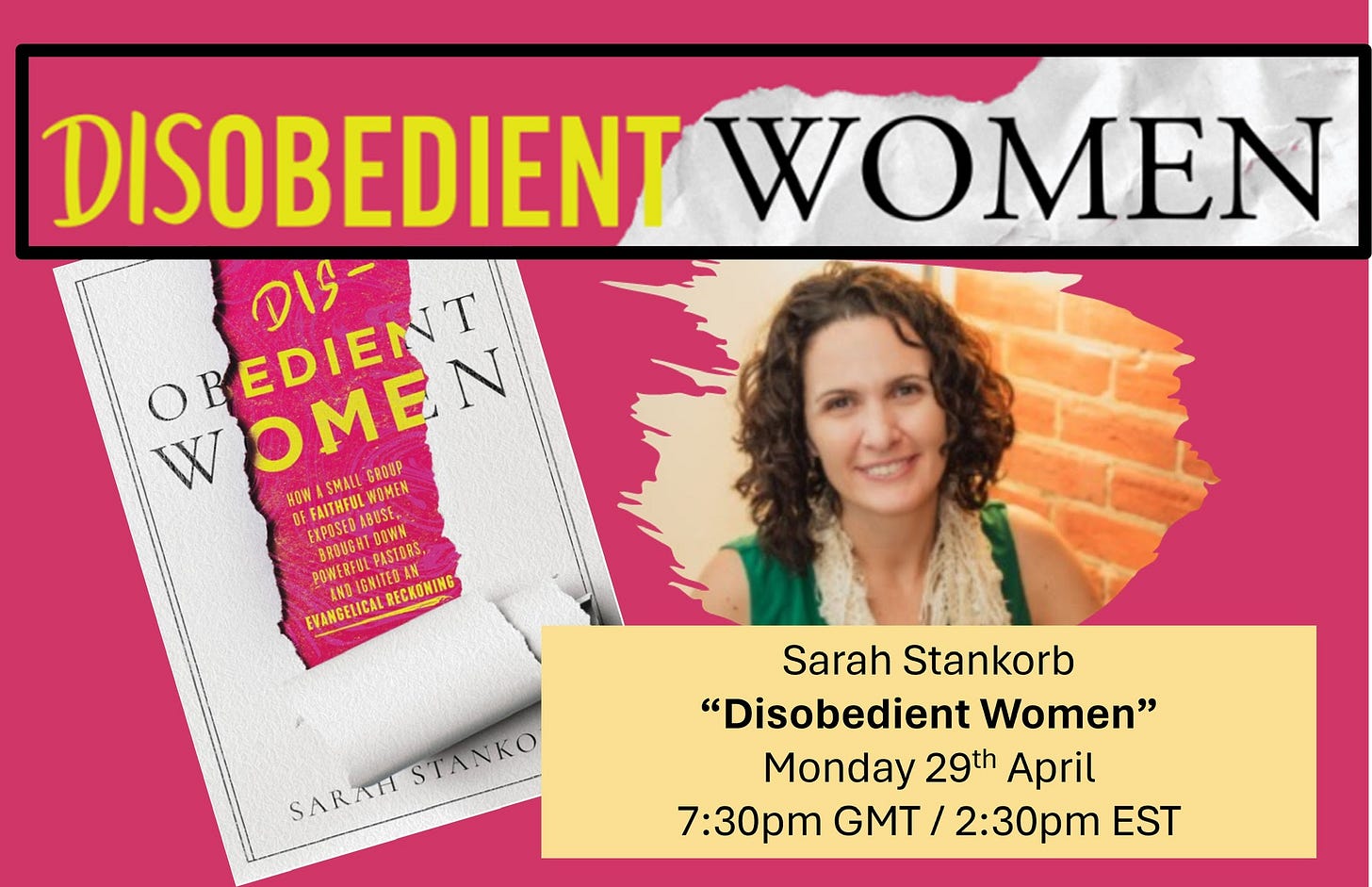

Readers of In Polite Company may be interested in joining the Feminist Theology Network. And if you do so soon, you’ll be invited to a book club session Monday, April 29 at 7:30 pm GMT/2:30 pm EST. (Yes! This network spans continents!)

When I write, I worry a lot about accuracy and doing right by the sources who trust me with their stories. I also spare space to think about the future reader. Will the article push them to action? Will they find a small mirror to their own lives in words strung together this way or that?

I can’t recall how I first got to know Cait West. It was somewhere online. Maybe it was her incisive social media posts. Perhaps it was a blogged narrative of her life inside Christian patriarchy. But I’ve known her name and snatches of her story for years.

It wasn’t too long ago that I discovered how she learned my name. Years back, I wrote a story for Marie Claire about stay-at-home-daughters, girls raised under the strict authority of their father until passed into the authority of their future husband. They were financially and educationally controlled. It was to protect them, so many evangelical books and films suggested. They could stay chaste and pure—unexposed to the lust of men and dangerous ideas like feminism and socialism. Cait read the Marie Claire story. She recently told me she remembered reading the article and, “I felt so seen by that, and it always stuck with me.”

This is the most any writer can hope for, giving a reader something to hold onto. But in watching Cait develop her own writing career, I’ve also gotten to witness a woman who was raised to be small and deferential grow into a sensitive and bold author. She is already giving her readers so much. Her new book, Rift: A Memoir of Breaking Away from Christian Patriarchy, debuts April 30. It’s a gorgeous book, that tethers together truths about faith and power with natural themes in a way that carries the truth of poetry and the heartbreak of memory.

I recently sat down to talk to Cait and wanted to share our conversation here.

The following has been condensed for length and clarity.

Stankorb: For those who don’t know you yet, could you please summarize your upbringing? Give us a window into what it was like?

West: I was born into a conservative Christian family, and baptized into a Presbyterian Church when I was a baby in Delaware. A lot of things about my childhood are fairly typical to evangelical homes. But the older I got, the more my family became involved in something called the Christian patriarchy movement. The idea behind this movement is that God is masculine, and the ultra-ultimate patriarch. And that's why men in this worldview were created as images of God, and made to be leaders in the world. Women, we were taught, were created to help men. They were created second, and so because of that, they are made to submit to men.

Stankorb: What was it like being a little girl in this culture?

West: Being a girl growing up in this movement meant that I was told I would never go to college or have a career, or be able to have a normal dating life as an adult. I would stay home until I got married. I was expected to marry someone my father approved, have as many children as possible, or as many children as God gave me, and homeschool them and continue to live this lifestyle of a woman living at home, very sheltered and protected. Looking back, now, I can see how that was very dehumanizing and oppressive. At the time, it was my normal. But I had to repress my sense of self just to survive that kind of environment.

Stankorb: One thing that came up a lot as I was reading the book was the media that gave a vision of what life should be like for Christians, specifically inside Christian patriarchy. I wonder if you could talk a bit about how the media influenced your family.

West: In the book, I talk about things like Patriarch Magazine and audio sermons from leaders like Doug Wilson and Doug Phillips. This was the material we had on hand all the time. I was immersed in these words about biblical patriarchy and what it means to be a biblical woman. I think my father was introduced to some of this by other men who were in the patriarchy movement and brought us further and further down this path.

It had this feeling of a grassroots movement of people who are passionate, and wanted to follow God the right way. It kind of felt like this club that you were a part of, if you knew the ‘real truth’ about the Bible and about God. And so it felt very special in that sense, I think that we are part of this bigger plan to spread this ideology. The leaders of this movement are very charismatic, very organized, they published books and magazines and made films and they created this whole environment to make it seem like a valid lifestyle choice.

Stankorb: From Rift and interviews with many other women raised like you, I have found such an urge to be good, do what you ought to do, are told to do, are told is godly. I wonder if you could talk about that rule-following impulse. How did it impact you or others raised like you?

West: I have two older siblings and I could see how they were bolder than I ever was, pushing the boundaries that my father had put on our family because we had very strict household rules. They were what my father would have called rebellious and what I would think of as having normal adolescent behavior. I could see them pushing against these boundaries and then my father punishing them for that. I did not want to experience that kind of shaming punishment. So I learned very early on that the best way to survive (though I didn't use that word at the time) was to conform to the rules. Because then I would be loved. I would be accepted. I would be blessed by my father and by God if I followed the rules. So I became very obsessed about following the rules to the point that I developed obsessive-compulsive disorder around very religious rituals and prayer and trying to be perfect all the time. And so that's how I integrated this environment for myself.

Some of my friends could never quite fit into the mold of what they were being told they needed to fit into. And they left a lot earlier than I did, because they couldn't survive this environment, and they needed to be their true selves. I think the difference is that I was very dissociated and repressed. And it was very unhealthy, to the point I became suicidal. So it was a very unsafe place for me.

I think other children have processed that in different ways. Because I don't think children are meant to be controlled to this extent.

Stankorb: Understood. Why don’t we change tacks a bit. You were homeschooled for all of school except part of kindergarten. Can you talk about the goals of homeschooling for you and how that impacted your relationship with your peers?

West: I was told homeschooling would protect me from teachings of evolution or teachings against religion, and things like drugs and sex and alcohol. That word protection was used, but what it felt like was isolation. I was alone. A lot of the time. I didn't have many friends. The only socialization I would get was either at church, or the occasional homeschool co-op group, where we would go and do a field trip together with other homeschoolers. And so that usually revolved around things like reading Laura Ingalls Wilder books together or visiting a museum. Those were really fun times for us. But they were few and far between. But it did enforce the fact that almost everyone I interacted with was in this world being fed the same information. So we didn't have any conflicting ideas. All of us believed the same things. And so I didn't develop a skill to discern for myself, what I thought was true.

Stankorb: What did it mean for your father to be a patriarch? For people who have not read the book, what does that mean in day-to-day life?

West: Every man in this movement who had children or who was married was the patriarch of their family. They were called to be the leaders of that home and were told that they were responsible to God, for their family. To the point that in my family, my father would say that he was responsible for my sinful behavior to God. So, that's a lot of pressure on these men, too, but my father's personality was already authoritarian. I can't speak for every man in this movement, but from my experience, my father, controlled every aspect of our lives, from what we were allowed to wear or listen to, or what movies we could watch, where we could go, who we could be friends with, what religion we believed in.

Everything on the surface went well when we followed his preferences without complaining. Over time, as I became an adult, it became a lot more difficult because he was controlling my romantic relationships. He was controlling who I was allowed to get married to, which, in a sense, controlled my entire future, and who I could become. He wouldn't allow me to get a higher education or get any work experience. His control in that sense is financial abuse as well, because I wasn't able to provide for myself. From the little things to the small things, there was a lot of control in my family. And I think a lot of the men in this movement, maybe not all of them but a lot of them, are very controlling. They're told to be that way.

Stankorb: Something that's difficult, if you've all you’ve known is the environment in which you grew up, is recognizing what is and is not abuse. I’ve interviewed many people who only reached adulthood and grasped the meaning of the word abuse before being able to put words to what they experienced. What was that realization like for you?

West: That resonates a lot with me, because the only idea I had of abuse was some kind of domestic violence situation where beatings were involved. So I didn't understand that there was a broader understanding of what abuse actually means until I was in my twenties and close to leaving my house.

I remember experiencing verbal abuse and emotional abuse, spiritual abuse, and not having the language for what that was feeling. Like. I just knew that it hurts, and it was making me feel like I was crazy. And I didn't know what to do. I felt stuck. I felt trapped inside of the small, little box my father was keeping me in. Until one day, I was able to search the internet and looked up some of these things I was experiencing. This article about emotional abuse came up. It was mind-blowing, because everything that was in that article had happened to me, and I finally had language to explain why I was struggling and suffering so much was not because I was crazy, but because somebody was inflicting this on me.

But I was very naive. I took that article to my father and showed him. I thought maybe I could explain why what he was doing was hurting me. But of course that backfired, and he was very upset that I would ever say he was abusive. Now I know that that's typical behavior of someone who is abusive. After I left I was able to do more research and understand the dynamics of power and control—and that abuse doesn't always have physical aspect to it. And so that was really liberating for me. It released all of that shame that I had.

Stankorb: Let's close with something really striking about the book, something you do so beautifully. Your prose returns again and again to nature, and I wonder if this was an attempt to give the reader somewhere to rest. Or was it that nature gives you somewhere outside to ground yourself and that creeps into the book? So much of this book is about power that is so personal and the lens is so close, then there are these pauses in places bigger and outside yourself. Was this habit? A way to root the reader? A literary device?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In Polite Company to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.