Before I get into the noise, if you’ve read Disobedient Women, please consider leaving an honest review at GoodReads, Amazon or with your favorite indie bookstore to help strike a balance.

I have a friend who encourages me to measure my success against the sort of detractors I attract. If a person who has done harm gets angry about you speaking truth, the logic goes, good. Keep it up.

Despite what the work I do might imply, as a person, I prefer not to agitate others. I possess a deeply ingrained fear of ‘getting in trouble.’ That’s likely why I find myself so fascinated by those who have a similar disposition and then make ‘good trouble’ anyway. There’s a delicate moment when the obligation to find and tell the truth overrides those impulses for quiet safety.

A lot of moral work happens in that tick between.

I was initially unnerved when Disobedient Women released to a warm reception. I was grateful to the new readers finding help and power in the stories. I was surprised not to be harangued. Maybe those inclined to do so had already wasted enough energy waving me off as a feminist (gasp!) member of “the media.” Likely, they knew noisy ire would inadvertently promote the book.

Over the past few months though, this tactic has begun reversing. Perhaps enough of you are reading and asking questions that it’s become necessary to attempt to dispose of my work. I’ve seen this sort of thing happen to other authors—namely

and . When smears are directed their way from evangelical leaders, it often comes with mischaracterizations of their work, some blatant misogyny, and questioning of their faith.I’m an agnostic, so that may make me easier to dismiss. Planted in a culture war that sees journalists as the enemy, the deal is the same there too. Alas though, the mischaracterization of my work has started to take off.

As my friend would tell me, I must be doing something right given where it’s coming from.

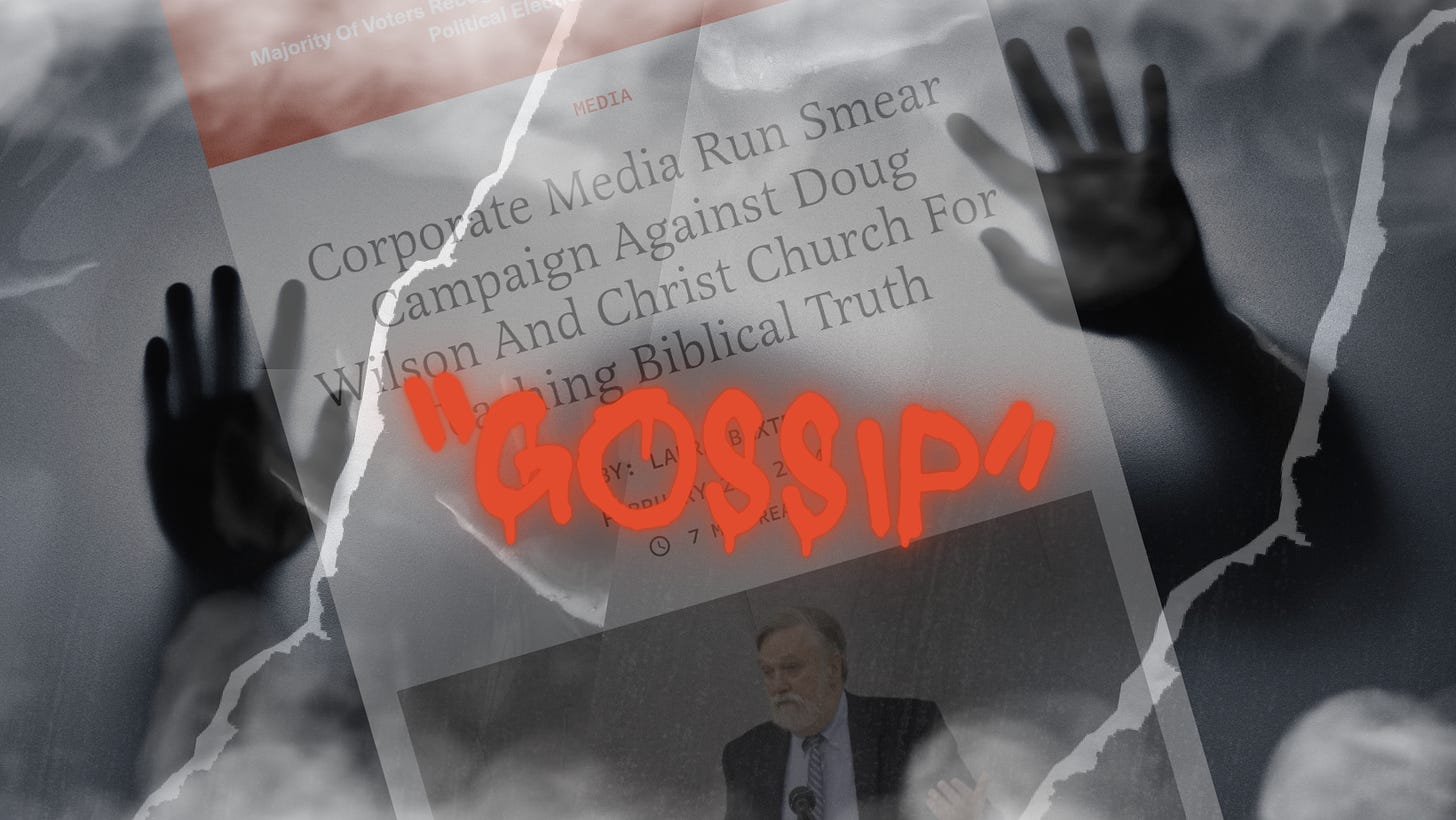

Recently a story published with The Federalist, called “Corporate Media Run Smear Campaign Against Doug Wilson and Christ Church For Teaching Biblical Truth,” claiming my reporting cherry-picks anonymous sources in my work on Moscow and Douglas Wilson, including Disobedient Women, wherein the author says, I “gossip.”

Almost every person I’ve interviewed who called out abusive practices in their church has mentioned that they were scolded for “gossiping,” for telling uncomfortable truths. So, I suppose this silly term was inevitable, applied wholesale to things we’d rather not hear.

If you’ve read Disobedient Women or even this older VICE article, I think it’s clear that the main concern of my reporting is not attacking “biblical truth.” I’ve collected stories of an initially attractive church culture that numerous sources describe as turning out, in their experience, to have been something quite different.

I hesitated to respond to the Federalist story. It’s a conservative news magazine that has helped spread COVID-19 misinformation, election fraud lies, and once published an essay defending Roy Moore for dating teens when he was in his thirties, because such an age gap is a good way to have a large family.

But I write for a lot of publications myself and wouldn’t always agree with the dumbest thing some publication I wrote for had also published, so let’s look at the piece itself.

The essay referencing my work was written by someone who says she moved to Moscow to join the church after “the Covid debacle, our pastors marched with Black Lives Matter and required masks for worship. We were devastated.” The author says she has enjoyed time with the Wilson family socially. In some ways, this makes her an interesting source from within a community I have covered who might have unique insights. She also makes clear her vantage point is one that remains comfortably aligned with her church leadership.

There are three main threads of critique that she raised that I thought could be useful to unpack, for this reader or any who comes with similar skepticism.

First, the author notes that I describe how I initially heard about Moscow from a person who did not seem well and whom I did not see as a good source. He was scared, maybe paranoid. I included this scene and my own skepticism upon getting to know this world of stories to illustrate that I wasn’t eager, coming in, to believe wholesale what I was hearing. I thought it was valuable to show, in this part of the book and as a cast to other sections, that while I am open to listen, I do not simply believe.

I thought it important to demonstrate that the reader too, is welcome to come in with their own skeptical lens. And ultimately, I included this example, because that’s how it happened. I was telling a true story about what I was told and how I suspected what I was being told was not the whole story—or might be false altogether.

I wanted to place bounds around what appeared to me to be credible and what didn’t, so when I did share information from sources I do deem credible, those lines would be clear.

Second, the essay writer complained that I relied on anonymous sources. I should point out that not all my sources were anonymous or asked for pseudonyms, and really, in my broader work on this community, the majority cited were comfortable being named even when it came at great personal cost. I’ll add that I have numerous other sources whom I spoke to on background whose stories I never published, some because they were not ready and others because they feared reprisal. I also interviewed numerous others because I just wanted to talk to many, many people to be sure that what I was hearing was indeed accurate. It’s part of doing your homework.

The decision for a source to go unnamed can be a tough one for a reporter and not a choice I take lightly. Additional credibility for the story can come with more people going on record with their names. Doing so can also change a source’s life forever, and I warn vulnerable sources that this is the case.

It is standard practice across many publications—The Washington Post, The New York Times—that when a source alleges sexual abuse, they are at liberty to go unnamed. This can be especially true when a child is the victim or the victim’s assault, when named, would link to the identity of their children. One of the women I cited in the book had a child as result of rape. When you consider how long things last on the internet, what information a child might find before a parent has time to help prepare them, I think most can understand such policies.

Another source I refer to, which used a pseudonym is a member of Examining Doug Wilson and Moscow (EDWAM). I explained that this group, which posts quotes from books and public records, has received numerous threats. Some are not pleased with what they do. Protecting the physical safety of any source is paramount to me.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In Polite Company to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.