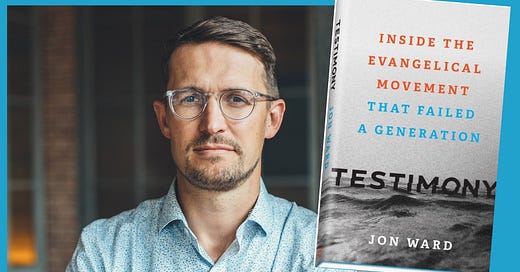

Invitation to Hear Testimony

An interview with Jon Ward about how evangelicalism failed a generation and journalism helped his faith

I had my own crisis of faith in the late 1990s, when the internet was solely for sustaining my AOL Instant Messenger habit. There was no online discourse about deconstruction. There were no books—at least none I knew about at my college out in Amish country—like Jon Ward’s Testimony: Inside the Evangelical Movement that Failed a Generation.

I wish there had been.

Ward, today the Chief National Correspondent for Yahoo! News, grew up firmly emersed in that evangelical world. The church was life, influenced how his family chose to educate him, the people he knew, and how he thought about his body and place in the world. In Testimony, Ward offers a raw look at what it’s like to begin to question the faith you’ve been given, but does so in the context of a person whose career gave him unique skills. Stepping into the world of journalism, Ward kept a critical eye and became aware of the limits of his own knowledge. Covering conservative voters, he had a reporter’s perspective on important undercurrents that would reshape our civic life. And then he found himself, the son of a former pastor, lumped in with other journalists as enemies of the people in the rhetoric of then-President Trump, and viscerally felt both the threat to our nation and the fracture within his own family.

Testimony is a gripping book that fights to hold onto what parts of faith still work, don’t cause harm, while functioning in a political reality that at times defies reason and so demands our best use of it.

is joining In Polite Company today to discuss some topics from his book and what he’s learned as a journalist, and how that impacted his faith.Sarah Stankorb: Some readers might recognize your childhood church, Covenant Life, as the church eventually pastored by Joshua Harris (of I Kissed Dating Goodbye infamy). But as an introduction to you and CLC, can you describe a bit what it was like for you growing up in such a closed community?

Jon Ward: On Halloween, we weren't allowed to go trick-or-treating. It was the Devil's holiday. So, a group of families from church would go to an indoor pool on that evening, to give us kids something fun to do instead.

One year on Halloween when I was probably 11 or 12, we were about to get in the car to go to the pool. I had my bathing suit on under some warmer clothes. It was cold outside, but I stripped down to my shorts and took a towel with me outside and ran across the street to a neighbor's house. I knocked on the door to trick or treat and told them I was a surfer. I only went to one or two houses, but I just really wanted to do it, even if only for a few minutes.

The only people I knew who weren't from church were kids I met in our neighborhood or on my sports teams. I played a lot of sports: baseball and football mostly.

I went to an elementary school run by our church. Students had to be children of church members. Teachers had to be members. The principal was one of the pastors. It was a very small world.

SS: I first got to know about Sovereign Grace Ministries (the church network for which CLC was flagship) through the hashtags (#IStandWithSGMSurvivors, #SGMSurvivors). Advocates demanding church sex-abuse reform whom I followed often took a chagrined tone about SGM, this megachurch network where abuse occurred, where there was clear evidence of failure to report (if not outright cover-up), but institutional-level justice never came.

You were the first baby dedicated at Gathering of Believers, which eventually grew into Covenant Life Church. You knew the place from the inside. Then later, as an adult, you had mostly moved on from CLC by the time leadership dysfunction and stories of abuse really hit the blogs and press. By then, do you think you'd gained the skills to look back at your church upbringing with enough of a critical eye to grapple with how different the church was from your childhood perceptions or were you still undergoing a process of disillusionment?

JW: By 2012, when my childhood church began to get dragged down by scandal, I definitely had analytical and critical thinking skills I had never been equipped with in church. And I'm sure that helped me in how I processed what was happening.

But it also boggled my mind how irrelevant so much of that church world was to anything outside it. The original scandal was not about sex abuse. It was hundreds of pages of allegations that C.J. Mahaney was proud by the standards of our church. And sure, C.J. was domineering and unaccountable. And later on we'd learn that the culture he built ran over victims of abuse.

But the hundreds of pages of internal memos and notes were depressingly, excruciatingly dumb. Instead of using church resources, time and talent to help people with their problems, the leaders were engaged in meeting after meeting that seemed comparable to Soviet era bureaucratic infighting. Just swap out the communist lingo for religious jingoism and cliches.

SS: I wonder if you'd talk a bit about your experience coming of age as a young man within the church. In the book, it struck me that you were immersed in a mix of New Calvinism (and a message that really you deserved death) and purity culture, that demanded perpetual confession for "impure" thoughts (or what most secular folks would consider normal sexual development and interest). When you were making such confessions and felt this way in the book, I believe you were an adult man, a virgin who hadn't kissed a girl in years. Reading your book, it seemed as if sin was doubly assumed, both by human nature and the specificity of being a young man. You wrote that "God is holy. We are worms," and it was heartbreaking.

How does a person come to terms with such a harsh worldview and try to find worth in themselves and start to see relationships as a healthy thing?

JW: It's been a long process, and I'm still on that journey. I've done some therapeutic counseling, but probably need to do a lot more. It's unfortunate that counseling can be so expensive.

I think this is one of the things I still find hard to talk about. It's very uncomfortable, highly personal, and it hurts to think about.

These ideas are so deeply embedded in my DNA, that it's very hard for me to dislodge them. I think this process is made more difficult because I'm very much not the type of person who throws babies out with bathwater. I am always trying to retain what's good and build on it, rather than just going a totally different direction, which to me seems inherently unstable.

It might help to tell a short story to illustrate the way these teachings and ideas are so hard to dislodge. There was a car that caught on fire near our house a few years ago. I woke up, saw the smoke and called the fire department. To this day, I go right past that spot many days while walking our dog. And even though this happened years ago, there is still silver metal that melted off the car, embedded in the concrete. It is really clinging to it. The years and the elements haven't managed to dislodge it.

That's what it feels like sometimes. Like, yes, I was taught to hate myself in some ways, but for a variety of reasons I can't just get rid of these thoughts.

SS: Wow. That is really powerful. I’m sorry. And I think a lot people feel that way.

JW: I will say I have found it very helpful to think about being kind to myself over the past few years, and I've discovered that this has come to mind as advice for others on several occasions.

SS: I've been researching the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR) for another project and was surprised to learn about Lou Engle's connection to CLC. You described vividly a period in the 1990s when a charismatic spirit swept through and it became something of a norm for people to make animal noises or laugh uncontrollably in the CLC sanctuary, overtaken by the Holy Spirit. On one side, is religious expression, and people should be free to tap into spirituality in whatever way seems to work for them.

But these activities get paired, by Engle and others within the NAR movement, with theology that also perceives spiritual warfare all around. They warn against Satanic attacks, then into 2016 and 2020, offered prophecies alleging Donald Trump's presidency was God's will. It shook me to see how this current was part of your church as a kid then tracked all the way up through the Jericho Marches and the Capitol Insurrection. Do you see it as the same or an evolving thread, and if so, I wonder how you see personal faith experience (and possible social pressure to perform that experience) might relate to the political. Do you think there is a degree to which coming to see the world in terms of a spiritual battlefield necessitates belief in some of the hard absolutes that have come to divide us as a people?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In Polite Company to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.