How History Shaped Evangelical Womanhood

A conversation with Sara Moslener, scholar of religion, gender, and racial discrimination.

Welcome back after an extended holiday break! For me, it was a needed one. The past year was busy, between family and writing my first book. Last week, a story I first pitched in 2021 finally published in VICE, profiling Christa Brown and featuring other figures central to sex abuse reform within the Southern Baptist Convention. A long-view story, I think it shows the toll of change on those fighting for reform and the moral debt we owe to all those who contribute to making our eyes see a path toward justice.

Today, In Polite Company takes an even longer view, sharing a conversation with Sara Moslener, a lecturer at Central Michigan University, where she teaches the history of religion and racial discrimination in the United States. Moslener is also the author of Virgin Nation: Sexual Purity and American Adolescence. Her current research, The After Purity Project, draws upon 65 interviews with people who’ve grown up and out of evangelical purity culture. Many of these stories will soon appear in her second book, After Purity: How White Christian Nationalism Exploits Race, Sex, and Religion.

I first spoke to Moslener years ago, when writing a feature for Cosmopolitan. We talked recently as I was sorting through how to place the stories in my upcoming book, Disobedient Women, in historical context. She made plenty of book recommendations, which I’ll share too.

This interview has been condensed.

Sarah Stankorb: I’ve been thinking a lot about trying to understand links and origins of various threads within evangelicalism. When I think about purity culture, I immediately consider Victorianism. That’s way back. How do the two connect?

SM: The argument I'm going to share is based on Gail Biederman's book Manliness and Civilization. She basically demonstrates the formation of Victorian gender roles and the cult of true womanhood—the Four Virtues, of which purity is one. What she argues is the true woman ideal was in response to the creation and the growth of the middle class in the 19th century. So, this is a class-based argument that she makes, and it is one that becomes about gender and about race.

In the 19th century, capitalism was growing because there was an enslaved workforce, which means white people were getting wealthy. White families were moving into the middle class and starting to be able to consume beyond their need. But there's a sense that there's a kind of disease with that, because it pushed against certain values—be humble, work hard, very early American, grit. So, there's a sense of unease, and especially because men were working out of the home. They were working in politics and commerce, and were having to do what could be considered things that lacked virtue. That’s just what is required to be in politics or commerce, right? That's necessary for the growth of the middle class, for the growth of capitalism. So, the way to balance is to pair the public man with the domestic woman who takes on all the virtues of goodness: piety, purity, domesticity, and submission. And the home becomes the center of spiritual life, not the church. (Now we’re getting into Douglas’s argument about the feminization of American culture.)

Victorians were essentially the 10%, if not less. They didn't represent most of the people, but they were the group that made it, which meant they were able to establish the ideals. And a lot of these ideals would be promoted in things like Godey’s Lady’s Book, which was the women's magazine of the 19th century.

SS: So, what ideals did magazines like Godey’s reenforce?

SM: This is where we get these notions of white femininity, what came to be known as “the angel in the house.” She stays home. She raises the children. She teaches and is in charge of her children's spiritual training. And so, the home literally becomes a sanctuary. There was a popular book, Treatise on Domestic Economy, by Catharine Beecher (sister of Harriot Beecher Stowe, who wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin).

Catherine Beecher was really prominent in her own right. Her book on domestic economy was basically about how to arrange your home so that it would become a sacred space. Victorian homes would often have a space, an entire room set apart, as a chapel. This is where we get the big family Bibles, because it was something to display in your home.

The idea was you marry the sort of public, rough-and-tumble unethical world that the man is in with the woman’s sanctuary of the home. That's the perfect combination, because then he can come back to his sanctuary and be grounded in the virtues there. But it's her job to make sure virtue remains in the home, that the home is a virtuous home.

SS: Everything you just said could be slightly updated as the voiceover on a Hobby Lobby commercial or an HGTV show. I’m feeling the virtue of a crafting room.

SM: That is so amazing. I feel so honored. Yep, yep. Live, laugh, love. That's exactly it.

The other thing is this is possibly also the origin for the purity culture assumption that women are responsible, and girls are responsible for the sexual purity of men and of men and boys. And that includes the assumption that oh, men just have to do this. This is what's necessary.

SS: Okay, so we’re to an economic structure that pigeonholes women and is rewarding white people. What’s next?

SM: White people begin to achieve middle class status in the 19th century—just really, upward mobility. People could at least work toward wealth. And so that mobility also becomes very protected in the same way that whiteness is protected. It was definitely part of the racialization of the American family, right in the family, the kind of family that was essential to a thriving nation state.

After emancipation, after Reconstruction, is when you get a surge in anti-miscegenation law. And there was a real effort. Slavery was created on a black/white binary. When that ended, they needed another way to maintain the race line. There were many ways to do that; anti-miscegenation law was one way.

The fear of race-mixing was reinforced by what Ida B. Wells called “the lynching myth” a popular trope that drew upon two powerful stereotypes: the sexually pure and innocent white woman and the aggressive, Black, male rapist. Rumors of clandestine relations or inappropriate exchanges were enough to insight white racial violence against entire Black communities. Pure, white womanhood was a propaganda tool for justifying white racial power.

In the 19th century, there was very much the sense of the white, Anglo Saxon Protestant family was the one that was most suited to growing civilization, and it was white women who were bearers of the civilization. Whiteness was all encoded in these gender ideologies, and they would be adopted and adapted, especially by the growing Black middle class in the early 20th century.

SS: So, how do we get from there to something like the 1920s and women’s suffrage?

SM: The ‘20s were a pretty vicious time, including intense anti-immigration laws being passed, intensive, immigration bans happening. I mean, you have Jim Crow laws in the South, you have segregation in the north, and it's interesting that at the same time, you have this sexual revolution happening, which is happening, really among white women, in at least for the benefit of white women.

The big change that was happening was separating marriage, sex, and procreation. That was sort of becoming newly accepted. And in part, because white women had increased educational opportunities and professional opportunities and were putting off marriage. This is the era of the New Woman.

Another book, I will recommend, set in that time period is called Righteous Propagation by Michele Mitchell, and it's about how the Black middle class adopted purity culture, created their own purity culture. It was all about ‘racial betterment,’ and helping upwardly mobile, Black people achieve middle class status. What's interesting about her framing is that she really does not talk about religion at all, and so it becomes this sort of economic argument. They're borrowing wholesale all the language from the white Victorians. But they're not using it in a supremacist way. They're using it as a form of racial justice, to say this is how we make our people better.

SS: Thinking of that time—the turn of the 20th century—that was the start of jazz music, right? For all the ‘scandal’ it was, wasn’t a big part of that racial mixing? But also—we skipped over something—where does fundamentalism fit in? Was it a response to everything going on in the culture or in some way a different response to Victorianism?

SM: Fundamentalism was responding to so many things. It was responding to science, of course, because you have the Scopes Monkey Trial. And then you have the response to the New Woman trying to change the gender roles. Also, at that time were debates over biblical interpretation. By this time, you have the academics who are interpreting the Bible academically, while fundamentalists believed that the Bible is one truth, and anyone can read it and know the truth. But academics were coming along and saying, ‘Well, no, the truth isn't self-evident,’ right? The Bible is a complex book, you need this special kind of training, if you want to understand what the Bible says.’ So, that was the huge clash. That really animated everything.

‘Gender roles’ became about protecting biblical gender roles and arguments about science were to come from the Bible. Fundamentalism was very much you know, a response to the more modernizing influences that were happening. The movement then sort of had this ebb after the Scopes Trial made them all look very foolish.

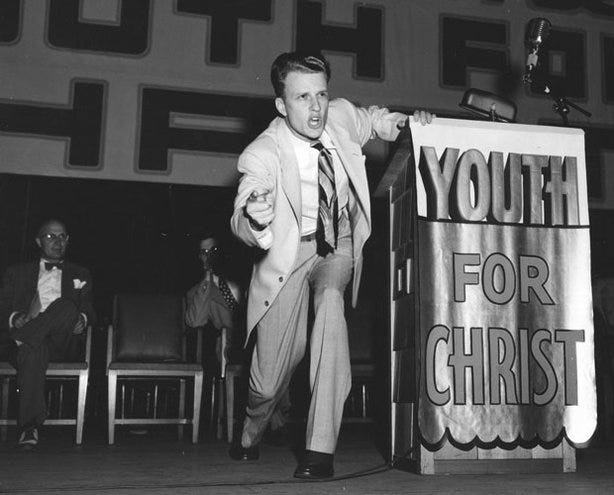

But Billy Graham comes in the ‘30s, with Youth for Christ, and makes it all hip and interesting again. He's someone who would go from being a fundamentalist to being an evangelical as a way to sort of bring fundamentalists out of their separatism. Which, of course, didn't work for everyone. There was still that hard line. This is also the time period when you see the growth of Christian colleges and radio—especially evangelical media. Evangelicalism was really kind of creating their own parallel institutions as a way to separate themselves from “the World.”

SS: Some of this sounds very similar to the Jesus People movement in the ’60s and ‘70s, a counter-counter-culture. Or the Christian right in the ‘80s. Just in a different time, the technology is different.

SM: What evangelicals do really well is marketing. For all Billy Graham’s influence, that really took off in ‘70s. I really like Mara Einstein's book Brands of Faith. She comes out of marketing and advertising and then writes about and studies religion.

“…that's when you get a church that looks like a mall.”

That’s why many of these evangelical churches were in the suburbs then. That's what Willow Creek did in the 70s. They went out to the suburbs, with a plan to plant a church out there. They did market research. They went door to door, and they asked people if they did or didn't go to church, and if not, why, and what they would want out of the church. And that's when you get a church that looks like a mall. Because people didn't want to go to a church that looks like a church.

There was still this idea within evangelicalism of having a family where the wife doesn’t have to work as a middle class goal. This period is also where I start to see an argument about white Christian nationalism develop, with this vision of the family as the foundation of the American nation state. And it's the white, middle class, suburban, heterosexual family.

SS: So, how did we jump to definitions of “biblical womanhood” that include wifely submission, with everything else going on—like the feminist movement—in the 60s and 70s?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In Polite Company to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.