SPOILER ALERT: If somehow you haven’t seen the Barbie movie yet, there are plot details ahead.

I was driving with my family through a deep red section of West Virginia on our way to the beach when we stopped for dinner and decided on impulse to catch Greta Gerwig’s Barbie. We were totally unprepared. Self-consciously examining the happenstance of our blue shirts as we joined a throng of eye-searing pink, my daughter whispered to me, “I feel like a couple of Ken stans.”

I was the sort of mother who had avoided Barbie altogether for years for my kid, only finally relenting to get her have a Curvy Barbie she rarely played with (the Barbie clothes she’d inherited fit the prototypically thin version). She played a little more with a campaign manager Barbie who came in a T-shirt and blazer, ready to help President Barbie with her campaign. That’s about as far as we got into a toy that I associated with body dysmorphia and a vapid cheerfulness. But I trust Gerwig. Whenever I need a good cry, I need only think of the scene of Jo’s bookbinding from Gerwig’s adaptation of Little Women.

In the early moments of the Barbie film, from the opening sequence spoofing 2001: A Space Odyssey’s Dawn of Man scene, I had tears in my eyes from laughter. I do not have what one would call a quiet theater laugh, and in our particular setting, in an unfamiliar town that was oddly quiet at the start, my daughter kept shushing me. When the Barbie Supreme Court heard an argument against plutocracy, I was audibly delighted. But soon enough, the rest of the room warmed up. It was suggested to me later that some of the laughter might have been directed at my own (loud) out-of-control giggles, but I’m certain it was Gerwig’s smart script, somehow balancing adoration for a nostalgic toy with stabs at the absurdity of Barbie’s influence in our culture—and the absurdities in our culture that create such impossible archetypes for girls and women.

It was unbearably silly, and it felt good, being in a more conservative setting, to see an entry point into discussion of gender equity and a crowd that grew increasingly receptive. Within the first 20 minutes, everyone was laughing and cheering. Equality should be a universally attractive theme.

In the film, Barbie’s world is a matriarchy, and the Kens are accessories that float in and out of the Barbies’ awareness. The gender flip from the real world outside Barbie Land only underscores the ridiculousness of any group holding dominion over another, while diminishing their potential. And it was all padded under blaring pink, silly costumes, and Ken’s ridiculous attempt at establishing a patriarchy in Barbie world. He doesn’t really know what to do with his newfound power, other than bro out Barbie’s dreamhouse into a Dojo Mojo Casa House.

Really though, all he’d wanted was to be acknowledged as a whole person. And understanding that makes Barbie grow too.

It’s a simple plot, as consumable as bubble gum, and that’s arguably what makes it so effective. The big ideas come dipped in pink sugar. Look what a mess patriarchy is (joke, goofy costume, joke). America Ferrera’s speech about the impossible bind of womanhood is both profound and widely applicable.

Satire is a vital, critical tool.

In 2017, pink was everywhere too. I was one of hundreds of thousands of people who flooded into Washington, D.C. for the Women’s March, anxious about what the future would hold, with a man being sworn in who had bragged “You know, I’m automatically attracted to beautiful — I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet. Just kiss. I don’t even wait. And when you’re a star, they let you do it…Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything..” Everywhere I looked, women were wearing hand-knitted or purchased pink “pussy” hats in various hues. It was a reclaiming, that much I understood. I also had no interest in wearing a vagina-inspired hat on my head.

But pink—which don’t forget, used to be considered a masculine color—has taken on a special significance for feminists.

Gerwig used Barbie as a vehicle to point out the absurdity of impossible gender standards, others take pink, so long used to indicate weakness, and claim it as a feminine symbol of strength.

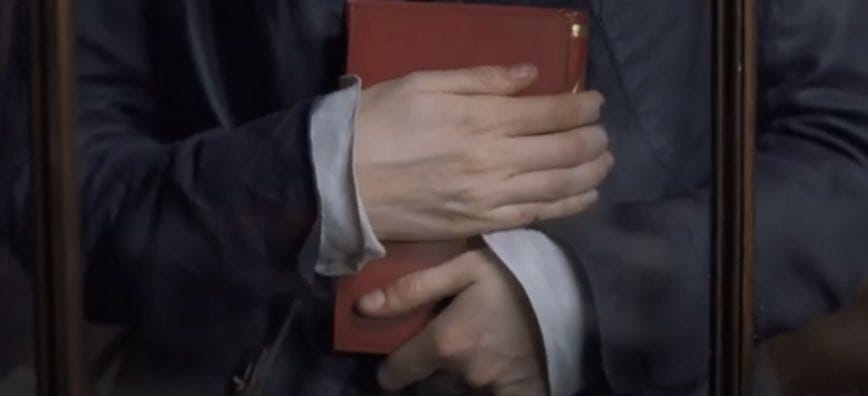

The color scheme on my own book, Disobedient Women, initially surprised me. I loved the faux-rip, the rupture and revealing of what was underneath conveyed in the design. But the pink gave me pause. (I’d been one of those moms who asked people not to shower our daughter with pink as an infant because I wanted her to have a whole spectrum of options from the start.) But Disobedient Women’s cover was so bright and eye-catching. I figured it would pop on a bookshelf.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In Polite Company to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.